16th century decorative plaster fragment from Warwick Castle

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

3 July 2025

In January 2025, a previously unknown plaster ceiling was discovered underneath the floorboards of a second-floor office. Conservation specialists were contracted to undertake important repairs to another decorative plaster ceiling (beneath the office) in the Cedar Drawing Room, a seventeenth century work commissioned by Robert Greville, lord Brooke (1638-1677) and undertaken by the instruction of local architects William and Roger Hurlbutt between 1668 and 1672. Two plasterers are named independent of the Hurlbutts: Edward Harding and John Hollis, but neither are specifically credited with plastering the Cedar Drawing Room.

On first inspection, the fragments of plasterwork were presumed to belong to the previous period of major architectural works at the castle, phased between 1605 and 1615 by Fulke Greville, lord Brooke (1554-1628), an aging Elizabethan courtier who had, by the end of his period of renovation, rose to become Chancellor of the Exchequer to King James I. But the decorative layout, symbols, and the rudimentary way the plaster decoration has been moulded all suggest this hidden plaster ceiling dates for the second half of the sixteenth century.

Decorative Plasterwork in Historic Buildings

Throughout the sixteenth century, architectural projects at country houses and castles were expressions of the owner’s political or dynastic success. Heraldry, coat of arms, and armorial symbols were routinely embossed into architecture, art, tapestries, furniture, armour, travelling cabinets, and portraits to demonstrate a courtiers’ legitimacy and authority. In the latter half of the sixteenth century, decorative plaster ceilings were an innovative craze that ‘Renaissance’ courtiers and ambitious magnates used to demonstrate their cultural attributes and elite tastes.[i]

Though some plasterwork examples predate this, most castles and royal manors were ‘sealed’ with highly decorative, mostly likely painted, timber roofs. The skillset of carpenters were far more highly prized than that of plasterers, and even by the reign of Henry VIII there were few skilled plasterers outside London. The emergence of plasterwork as a fashionable interior decoration was in part thanks to changing attitudes to the domestic sphere, the embrace of Renaissance ideals, and the break with the Roman Catholic Church. Though plasterwork could still be painted, whitewashed plaster ceilings grew in popularity in the late sixteenth century, partly for practical reasons (white finishes enhanced light levels in grand chambers more likely used for social rather than political purposes) and partly as an expression of Protestant virtues and the literal ‘washing away’ of medieval Catholicism. In 1598, the Italian Giovanni Paolo Lornazzo wrote ‘White, because it is apt to receive all mixtures, signifieth simplicity, purity, and elation of the mind.’ Taken together, ‘white’ was an expression of the most ‘noble and worthy.’[ii]

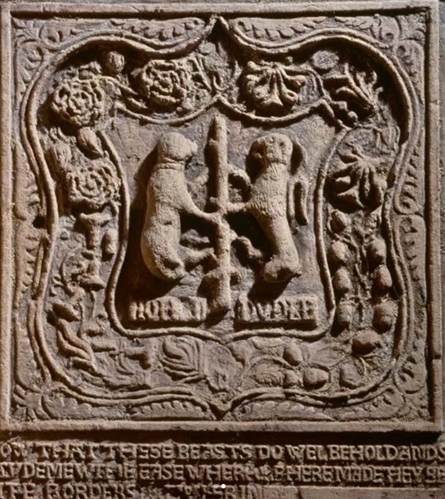

From the innovations of Cardinal Wolsey’s interiors onwards, and particularly in the 1570s and 1580s, plasterwork designs were modelled on details found in antique ruins found during mass excavations of old Roman buildings during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Renaissance décor was used by England’s nobility as an expression of cultural superiority and loyalty to the monarchy. Perhaps more importantly, in the case of the Warwick plasterwork, is the popularity of heraldry and ancestral devices in sixteenth century plasterwork, where intricate details and mottos could be moulded with more efficiency than those carved from timber. Surviving examples such as the duke of Norfolk’s interiors at the Charterhouse in London (1565-71 – Fig. 4), Ormond Castle in Ireland (c1575), and Theobalds in Hertfordshire, remodelled by the Cecils for Elizabeth I’s state visit in 1571, can still be seen today, as is the sixteenth century frieze at King’s Manor in York, which includes the badge of the Bear and Ragged Staff (Fig. 1).

There are a few rare plaster ceilings that survive from the 1540s and 1560s, but these show the practice of decoratively plastering a ceiling was still rather unsophisticated and lacked the detailed precision of those later in the century. Earlier examples include a fragmentary ceiling at West Horsley Place in Surrey (c1547 – Fig. 2) with a ribbed patterns laid out inelegantly and dotted with heraldic badges. The Long Gallery at Holcombe Court in Devon has an ungainly design from sometime before 1566 and shares no relationship to the innovations of plasterwork at the Tudor court (Fig. 3).

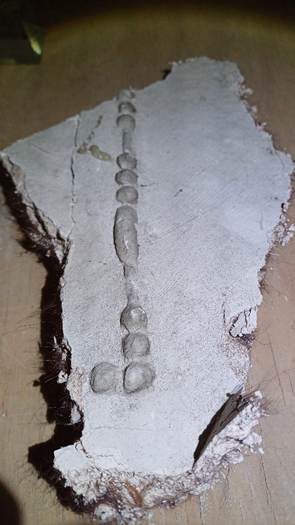

The composition of the rediscovered plaster fragments correspond to the composition of other surviving plasterwork of a sixteenth century date. It is made from lime plaster and oxen hair (Fig. 6). Lime was popular for moulding and sculpture, as it was slow-setting which gave the plasterer time to work on the finer details before it dried extremely hard and durable. The Warwick fragment shows evidence that sandy clay and Ox hair have been beaten into the plaster to increase its durability. The beading on the border was likely made by hand, due to the inconsistent and unsymmetrical layout, a theory only ascertained with further fragmentary excavations. The process of producing lime plaster for plasterwork has been detailed by Dr Gapper in her PhD.[iii]

In all these cases, surviving sixteenth century plasterwork is still in situ. Due to its delicate production, there is only a few surviving ‘loose’ plasterwork fragments from the sixteenth century.[iv] The survival of the Warwick plasterwork is extremely rare in England, and can be of essential academic value to scholars who might wish to study sixteenth century interior decoration, architects to explore how plasterwork was installed and protected, and traditional craftspeople to examine how early plasterwork was formed and made.

The Warwick Plasterwork symbology

The plasterwork detail forms a diamond with classical border and a large central motif and two smaller emblems either side. The central motif is clearly identifiable as the Warwick Ragged Staff (Fig. 5). It is not entirely clear when the Ragged Staff became a local emblem, but it was in popular use by the late fourteenth century. According to the antiquarian John Rous (d1492), whose Rous Roll chronicles a dynastic history of the House of Warwick, the Ragged Staff derived from the legendary Gwayr, a Saxon warlord from the age of King Arthur who ‘met with a giant that ran on him with a tree shred of the bark…[he] overcame the giant, and in token thereof bore in his arms a ragged staff of silver.’[v]

More recently, the historian Emma Mason has proposed the Ragged Staff may have been inspired by the medieval romance Gui de Warewic, in which the protagonist Guy of Warwick used a tree trunk to defeat a Lombard knight and subsequently employed the trunk as a staff while on pilgrimage.[vi] It may be that one of these stories inspired the other; and came to be adopted by Thomas Beauchamp the elder, earl of Warwick (1313-1369), a prominent magnate at the court of Edward III, who was himself engaged in associating the royal Crown with Arthurian legends.[vii] Either way, by the end of the fourteenth century Warwick town had claimed as its coat of arms a black shield bearing a white Ragged Staff, while the earls of Warwick amalgamated the symbol into a new badge combined with their ancient heraldic symbol of the Bear. The will of Thomas Beauchamp the younger, earl of Warwick (1338-1401), recorded several prominent ‘ragged staves’, presumably long, carved staffs carried by his officials during ceremonies and public occasions – similar staffs were made for Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester’s ceremony of the Order of St Michael, held at St Mary’s Church in Warwick on 29 September 1571.[viii] By the 1430s, the Bear and Ragged Staff was the badge of the House of Warwick, and steel or silver badges of the Ragged Staff were given out to retainers and contracted warlords throughout the fifteenth century.

Despite securing Warwick Castle from the Crown lands in 1604, Fulke Greville is not known to have adopted the Bear and Ragged Staff as his own device. There may be several overlapping reasons for this. Fulke, like his father before him, had made claim on the castle through a weak, almost tenuous bloodline back to the medieval earls of Warwick (a genealogy that had to stretch back nearly four hundred years). Fulke’s father had complained of significant disrepair, and that unless serious action was taken ‘there would be nothing left but a name of Warwick.’[ix] When Fulke eventually inherited Warwick Castle, he made no claims on the Warwick earldom which was also in abeyance. It is likely Fulke felt unable to seek the earldom when several high profile courtiers and friends had a greater claim; not least the Sidney family. Indeed, Fulke’s best friend Philip Sidney (1554-1586), the famous poet who had died a Protestant martyr in 1586, had been one-time heir to the Warwick earldom (his travelling trucks used at Shrewsbury School, where he enrolled with Fulke, were embossed with the Ragged Staff emblem).[x] Fulke’s personal motto, Vix ea Nostra Voco translates as ‘I Scarcely Call These Things my Own’, perhaps a solemn acknowledgement that he was simply the ‘steward’ of what should have been Sidney’s legacy and inheritance.

While the Ragged Staff is clearly identifiable, the two symbols either side are less certain. An early theory that they were the symbols of the Rosicrucians can be easily dismissed; the other that they were Masonic or Guild marks less so. It is entirely possible they are such marks, but it is more plausible the symbols form the decorative shape of two letters:

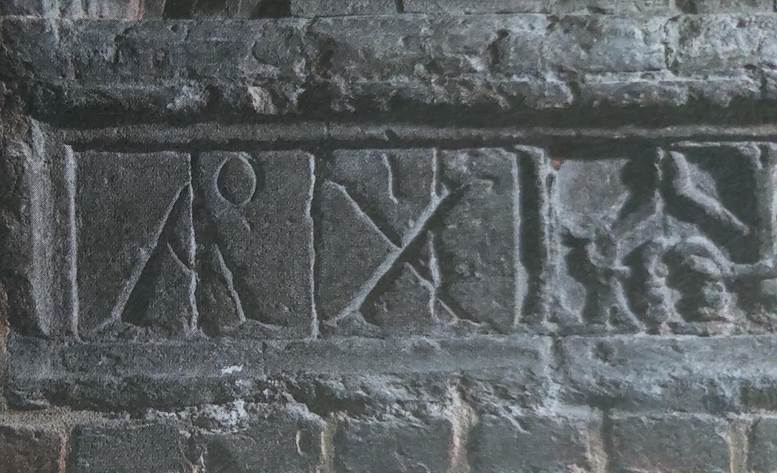

A and W

While the ‘A’ has the distinctive shape of a masons’ tools, it was nonetheless an anachronistically popular and stylistic way of drawing an ‘A’ in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Fig. 7). There are a few surviving mouldings in the same style, such as decorative brick from the London docklands dated c1513 (Fig. 9) and a plaster frieze at Wimborne House date c1600 (Fig. 10). Chalk graffiti in Warwick Castle’s Guy’s Tower dated 1649 also uses the same style. More importantly, a decorative A in the same design survives on one of Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester’s fireplaces at Kenilworth Castle (Fig. 11). The ‘W’ appears to be shaped by ragged staffs weaving around one another, imitating the same style as Leicester’s fireplaces at Kenilworth (Fig. 11). Architectural historian Jonathan Foyle has convincingly shown that sixteenth century courtiers adopted anachronistic typographies and patterns in their art and architecture, particularly those who sought to demonstrate their dynastic antiquity and legitimate right to rule.

Ambrose Dudley, earl of Warwick

The commonality of composition to late sixteenth century plasterwork, the use of the ragged staff symbol, and the anachronistic A and W lettering all suggest the plaster ceiling were commissioned by ‘Ambrose Warwick’, that being Ambrose Dudley, earl of Warwick (1530-1590).

When Ambrose was born, his father John Dudley (1504-1553) had already set his sights on Warwick Castle and the Warwick earldom. John’s mother Elizabeth Grey was the great-granddaughter of Margaret Beauchamp, eldest daughter of Richard Beauchamp, earl of Warwick (1382-1431). He may have inherited his great-grandmothers’ grudge at losing out on the Beauchamp inheritance in 1449, when Margaret was (rightly) overlooked for her younger half-sister Anne, who had married Richard Neville. Margaret eventually sealed a settlement with Neville in 1466, acknowledging his right to the inheritance, and only after his line was extinguished could the Warwick inheritance revert to her heirs.[xi] In his petition to inherit Warwick Castle, John wrote the Privy Council: ‘because of the name and my descent from one of the daughters of the rightful line I am the more desirous to have the thing’[xii] The course of his career suggests he fancied himself a new Richard Beauchamp: just as his ancestor had been a loyal soldier to Henry V and a tutor and guardian to his heir Henry VI, so too John had been a loyal enforcer for Henry VIII and became the Lord Protector for the boy king Edward VI in the 1550s.

But John’s position was undermined by his lack of title and lordship that senior figures of the Privy Council traditionally had. In 1532 he secured the office of Constable of Warwick Castle and Keeper of Wedgnock Park, two offices held by the Crown after the medieval earldom went into abeyance in 1499 (the Warwick lands had already been granted to the Crown in 1487). In 1547 he secured the earldom of Warwick, and two years later the outright ownership of Warwick Castle for his family. Ambrose followed in his father’s footsteps, inheriting the earldom of Warwick and the castle in 1561-2 with the acquiescence of Elizabeth I.[xiii]

The Bear and Ragged Staff badge was an essential part of the Dudley’s authority and myth-making. The earliest known use of the badge came in 1549, when the symbol appears on a charter of John Dudley, earl of Warwick. In 1553, an inventory of his goods reveals ‘two pieces for the base of the same bed likewise embroidered with the ragged staff.’[xiv] Graffiti of the ragged staff survives in the sixteenth century apartments of Hampton Court Palace (Fig. 13), presumably left by a Warwick retainer during John’s role as President of the Privy Council under Edward VI. A second use of the device is scored into the second-floor chamber of the Beauchamp Tower in the Tower of London (Fig. 14), left by Dudley’s four sons during their imprisonment after his failed efforts to secure the Crown for Lady Jane Grey in 1553. Only in December 1561, three years into Elizabeth I’s reign when the young queen felt confident the controversies over John Dudley had passed, was Ambrose restored with the Warwick earldom, and then a year later Warwick Castle, and in September 1564 his brother Robert Dudley was granted the earldom of Leicester and Kenilworth Castle: the two brothers sought to imitate the first Norman conquerors in the region, Robert and Henry of Beaumont, the earls of Leicester and Warwick in the early twelfth century. They were the only men created earls, where neither had previously been barons, by the Tudors in the sixteenth century.[xv]

Both Ambrose and Robert were active enthusiasts for exploiting the artistic symbolism of the Bear and Ragged Staff. Robert’s use is better known: in 1568 he received a bill to produce silver badges of a ragged staff to be worn by his retainers and officers, and ceremonial white staffs were carried by his steward, treasurer and controller.[xvi] A tilt armour dated to 1570, held today in the Royal Armouries, is etched with ragged staffs. The inventory of Kenilworth Castle 1578 records cushions, chairs, pillowcases, velvet canopies, bed linen, cloaks, nightshirts and other household items ‘embroidered with the bear and ragged staff in silver.’[xvii] A portrait of Robert’s wife Lettice Knollys, countess of Leicester, dated to 1585 shows her in a bodice embroidered with ragged staffs. Catheryn Enis’s excellent survey of the Dudleys in Warwickshire demonstrates how the incessant use of the device was less to convince themselves as everyone else of their legitimate right to claim the ancient earldoms of Leicester and Warwick.[xviii] The two brothers faced fierce opposition to their inheritance, not least from members of the gentry in Warwickshire who were riled by the imposition of the courtiers into local political affairs, not least Edward Arden who had his own legitimate claim on the Warwick earldom.[xix] Yet while Leicester’s dynastic cultural war is well-known, Ambrose’s attitude and exploitation of the ragged staff is less well-known.

Ambrose was aggressive in his assumption of the political and landed power of the Warwick earldom. A survey commissioned in 1576 was laced with the language of feudalism, suggesting his tenants and retainers owed him fealty by consequence of their rental agreements.[xx] He aggressively pursued his rights to rule the town corporations of Warwick and Stratford-upon-Avon, which earned a sharp rebuttal by the wizened Thomas Oken in 1571.[xxi] A riot at Myton in the late 1570s could also be linked to Ambrose’s imposition of the Warwick Corporation, as burgesses loyal to the Dudleys faced off against those who opposed them.[xxii] Besides his decorative tomb in the Beauchamp Chapel, commissioned and completed after his death in 1590, and the survival of a ceremonial sword (to be worn while riding) with a decorative bear for a pommel and ragged staff guard which may have belonged to him, there has been scant surviving evidence to suggest Ambrose was as forward in his associations with the ragged staff as his younger brother.

The discovery of this plasterwork, if from the tenure of Ambrose, would suggest that he was more expressive of his dynastic inheritance through the symbology of the Ragged Staff than previously thought. It would be his only surviving architectural commission.

Ambrose Dudley and Warwick Castle

The established narrative of sixteenth century Warwick Castle has been one of ruin, disrepair, and neglect based on several remarks made throughout the sixteenth century to its general decay and poor condition.[xxiii] Sporadic repairs were made by royal glaziers and masons through the early sixteenth century. The first notable description was made by John Leland during his itinerary of the West Midlands sometime between 1536 and 1543. He described how ‘the dungeon [presumably a lost tower on the north-west wall] now in ruin stands’ and ‘on the south side of the castle, the king does much cost in making foundations in the rocks to sustain that side of the castle, for great pieces fell out of the rocks that sustain it.’[xxiv] Repairs, and possibly a full reconstruction, was made to the kitchens in the 1530s, re-roofed using tiles taken from the recently abolished monastery of St Sepulchre on the north side of Warwick.[xxv] In 1547, in a letter written by John Dudley he claimed the castle ‘is not able to lodge a good baron with his train, for all the one side of the said castle with also the dungeon tower is clearly ruinated and down to the ground.’[xxvi] In 1590, a survey recorded considerable decay to the building. In the ‘Paved Hall’ two large windows had collapsed and ‘in such decay that if they be not repaired they will not stand till the next spring’, and the led roofs on the chapel, gatehouse and Caesar’s Tower had leaked. A gallery running from the Great Chamber to the Chapel had lost its timber roof, and a timber bridge connecting the domestic buildings and the Watergate Tower was ruinous. The Spy Tower, established sometime between the life and death of the duke of Clarence and Henry VIII, was ‘wasted’ and the ‘stone wall thereof is decayed and ready to fall down.’[xxvii]

The extent of deterioration to the fabric of the building at a time when the Dudley brothers were trumpeting their historic associations with the House of Warwick has always seemed contradictory. It is possible the brothers’ deliberately ‘aged’ Warwick Castle, seeking to emphasis and exaggerate its antiquity (and therefore their own ancestral antiquity): it was in the late sixteenth century the south tower was first recorded as ‘Caesar’s Tower’, during a period when more and more English courtiers and town corporations sought to demonstrate their Roman ancestry.[xxviii] Robert Dudley’s Kenilworth Castle also had a Caesar’s Tower. Similarly, and during Robert Dudley’s major renovation at Kenilworth castle 1570-72, the old Great Hall of John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, was left entirely untouched and unrepaired, and new works were designed to imitate and complement the existing fourteenth century designs.[xxix]

With the numerous reports of disrepair made before 1590, it is easy to believe that the entire castle was in serious decline throughout the sixteenth century. But the sources for the deteriorated state must be taken with caution: each report had its own agenda for exaggerating the poor condition of the building. It was still suitable enough to welcome Henry VIII’s household during a royal progress in September 1511 and the antiquarian John Leland described it as ‘a magnificent and strong castle’ in the late 1530s. Warwick Castle was also able to host a royal visit from Elizabeth I on two occasions, firstly in 1566 and then for a secondary visit in August 1572, in which visit the Queen slept in the chambers at the castle too.

Elizabeth I’s State Visit to Warwick, 11 – 18 August 1572

The likeliest date for the commission and completion of the Warwick plasterwork was to coincide with the state visit of Elizabeth I in 1572. The only known reference to architectural work made by Ambrose Dudley at the castle occurred for the same visit, referenced in a letter written by Fulke Greville the elder to Sir Robert Cecil on 17 October 1601. In it he reported the parlous state of the castle, describing ‘the timber lodgings built thirty years agone for herself [the Queen], all ruinous.’ A survey of 1576 describes ‘the Queen’s gardens next Avon without the castle wall’, suggesting new gardens were laid for the Queen at the base on the Watergate Tower, though these had disappeared by c1600. The 1590 Survey described a wing of the apartments as ‘new buildings’ and in 1604 a survey noted ‘the timber work thereby in many places rotted especially in the principal parts called the Queen’s Lodgings.’[xxx]

These works at Warwick Castle align chronologically with major renovations undertaken at Kenilworth Castle for Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester, between 1570-72. Leicester’s ‘new buildings’ were erected onto the eastern end of existing medieval state apartments, a four-storey tower with an undercroft, principal apartments, bedchambers, and an upper floor for service and household utilities. A new entrance doorway was knocked through from the old apartments to the new, and contemporary records of Elizabeth I’s visit in 1575 described her processing through the medieval Great Hall, Great Chamber, and Privy Chamber before crossing into her dining room and bedchamber within Leicester’s wing (Fig. 17). Leicester also commissioned a new gatehouse, which is somewhat of an imitation of Warwick Castle’s Great Gatehouse (Fig. 18), new stables, and modifications were made to the windows of the Great Hall. There is speculative evidence that Leicester also modified the interior décor of the Great Chamber and Privy Chamber too.[xxxi]

This may have included plasterwork: a plaster ceiling is recording at the head of the staircase leading into the Great Tower, and surviving dowel holes above the fireplaces of Leicester’s new buildings suggest a plaster overmantel or frieze may have been secured there. Much later, on 26 May 1579, an inventory from renovations at Chatsworth House record payment to ‘John plasterer to pay the plasterer that he brought with him from Kenilworth.’[xxxii] Though little of Leicester’s interior decoration survives, the propensity of carved ragged staffs in stonework and fireplaces dating to the 1570-72 renovations hint at the expansive use of the device in interior decoration by Leicester at Kenilworth Castle. Elizabeth Goldring notes the integration of initials, badges and emblems into window jabs, chimney-pieces, garden fountains, and furniture typical of his architectural ambitions, the fusing of dynastic mythologies and princely magnificence.[xxxiii] Indeed, the anachronistic use of the ragged staff in the letters R and L throughout are coeval to the stylistic A and W of the Warwick plasterwork (Fig. 12).

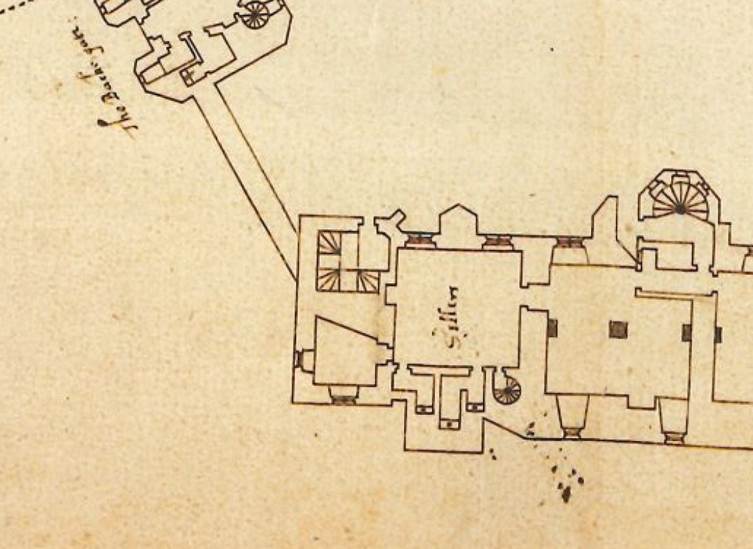

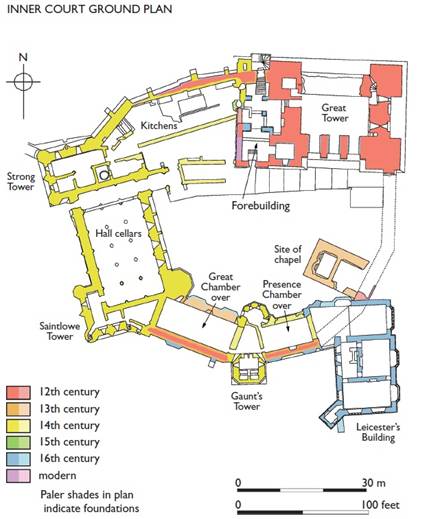

The likeliest location of Elizabeth I’s ‘timber lodgings’ erected by Ambrose Dudley are those of the south-west corner of the courtyard, abutting the western end of the medieval state apartments. The layout and design of these apartments are hinted in theSmythson Plan, a floor plan of the ground floor of the castle made in c1600 (Fig. 15). The ground floor and foundations were constructed in sandstone and show evidence of cutting across the original line of the medieval rampart between the domestic apartments and the Watergate Tower, known in the sixteenth century as the ‘Tower over the Iron Gate’ that led to a small garden on the riverbank (Fig. 16).

In Booth’s survey of the Watergate Tower, he notes a timber bridge connected Elizabeth I’s lodgings with the fourteenth century Watergate Tower, suggesting the tower interiors may have been furnished for the royal visit, perhaps for important courtiers or her ladies in waiting, perhaps even for the Queen herself.[xxxiv]

The basement has several important features to mention:

- Square staircase: the large staircase connecting the courtyard to the upper apartments was a popular architectural feature of Elizabethan country houses and was extremely rare prior to the mid-sixteenth century. Cardinal Wolsey’s apartments at Hampton Court, for example, the highest and most innovative Renaissance architectural design of the early sixteenth century, still adopted turret stairs.[xxxv]

- Northern oriel window: the northern pointed-jutty suggests this may have been the foundation of a large oriel window, a popular Elizabethan design, that was known to be a prominent feature of Leicester’s new buildings. It would correspond with evidence from The Black Book of Warwick that described the Queen watching a performance of country dancers in the castle courtyard from a window.[xxxvi]

- High quantity of garderobes: the plan shows three individual garderobes inside the new undercroft, suggesting it was expected to be populated with a high number of staff, presumably those serving the royal apartments above.

Though nothing of those Elizabethan apartments survive, future architectural renovations might hint to their possible use when compared with the layout of Leicester’s new buildings:

- Queen Anne Bedroom: may have functioned as the Queen’s private dining room. This would correspond to Fulke Greville’s upgrade of the chamber as a ‘new dining room’ between c1605-1615; he may have attended the Queen’s state visit in person.[xxxvii]

- Panelled ‘finance office’: as one of the grandest suites on the third floor this may have functioned as the Queen’s bedchamber. It is recorded in The Black Book of Warwick that the Queen viewed a performance of fireworks and mock battles from a balcony in her private chambers: this may be the recess in the Queen Anne Bedroom or the finance office.[xxxviii]

Such suggestions are merely speculative, but if these apartments had originally been the temporary timber lodgings erected by Ambrose Dudley, it is almost certain he was responsible for creating the doorway between the modern Queen Anne Bedroom and the Green Drawing Room. The Green Drawing Room was probably the medieval Privy Chamber, where a turret stairs led up to the grand Bedchamber for the medieval earl or countess, today the Italian Library. Like Leicester, Ambrose likely added embellishments to the Presence and Privy Chambers where the Queen would have sat in state for her courtiers and the local dignitaries. A decorative plaster ceiling that strengthened the historical associations of the Dudleys to their medieval forebears, in the chamber where important courtiers and local officials were gathered, would have been entirely consistent with the approach taken by both Dudley brothers in their architectural and artistic propaganda.

Last minute decorative commissions?

The fairly limited decorative design, hand-made beading, and the rudimentary care of the final installation all suggest that Ambrose Dudley’s dynastic plaster ceiling was completed in a rush. There is similar evidence of hastily finished stonework at Kenilworth Castle, which would support the hypothesis they were commissioned for a specific date, namely a royal visit. Elizabeth I was well-known for scolding, or mocking, her courtiers’ accommodation if she felt it beneath her royal dignity. In 1569, the Queen mocked Sir Nicholas Bacon’s home at Gorhambury: ‘what a little house you have gotten,’ she remarked, forcing Bacon to commission a long cloister and gallery ready for her second visit.[xxxix] In 1576, when Elizabeth I remarked a chamber at Thomas Gresham’s Osterley would look better divided, he hired workers to partition the room overnight to impress to Queen.[xl] Elizabeth I made similar disparaging comments about Kenilworth Castle before her visit in 1575, and it is possible she visited the castle in 1572 to inspect the ongoing works. It is not known if the Queen made similar remarks about Warwick in 1566, but it is entirely plausible. Such was the anxiety over the Queen’s unhelpful honesty, many courtiers or country gentlemen found excuses to avoid hosting a royal progress altogether, such as the earl of Bedford in 1572 who advised his house at Woburn was still unfinished or the bishop of Winchester who encouraged the royal party to stay away because of plague in the nearby towns. Others used their welcoming speech to pre-emptively ‘apologise’ for the poor or ruinous condition of their estates.[xli] Indeed, during her visit to Warwick the town Recorder made repeated apologies for the ‘poor town’ she was about to enter, and Ambrose wisely retired to the Priory for the duration of the visit, perhaps to avoid such criticisms of his castle.[xlii]

It is therefore entirely possible that the construction of a timber lodging to house Elizabeth I was a consequence of the need to provide her with suitable royal interiors, but with limited time to complete a construction on the scale of Leicester’s new buildings. The rudimentary design of the Warwick plasterwork, with its classical border seemingly improvised and made by hand rather than a mould (Fig. 8), might also hint at the hastiness of Ambrose’s interior upgrades, although without further samples to compare this is merely speculative.

Conclusions

In summary, the Warwick plasterwork is:

- A remarkable and rare survival of sixteenth century interior design, and one of the only known ‘loose’ plaster fragments from Tudor England.

- Has rudimentary patterning, simplistic classical border, and whitewash finished – all highly suggestive of a c 1560s or 1570s construction.

- Consistent it its symbology and anachronistic decoration with the Dudley’s architectural and artistic style during the 1570s and 1580s.

- Likely part of the work commissioned for Ambrose Dudley’s interior modifications in preparation for the state visit of Elizabeth I in 1572.

- The only known interior decoration to survive from Warwick Castle dated pre-1605, an extremely rare example.

Aaron Manning

June 2025

Appendix: Images

Fig 1: Detail of plaster frieze at King’s Manor, York, sixteenth century

Fig 2: Plaster ceiling at West Horsley Place, Surrey, c1547

Fig 3: Plaster ceiling at Long Gallery, Holcombe Court, Devon, c1566

Fig 4: Detail of bay window plaster ceiling commissioned by the duke of Norfolk, Charterhouse London, c1571

Fig 5: Th Warwick Plasterwork, full excavated fragment

Fig 6: Detail of Ox hair and lime plaster material

Fig 7: Detail of the decorative ‘A’ on the Warwick Plasterwork

Fig 8: Detail of the classical beading on the Warwick Plasterwork

Fig 9: Decorative ‘A’ on brick from London Dockyards, c1513

Fig 10: Decorative ‘A’ in plaster frieze at Wimborne House, c1600

Fig 11: Decorative ‘A’ interwoven with ragged staffs at Kenilworth Castle, c1570-1

Fig 12: Decorative ‘R’ and ‘L’ using anachronistic ragged staffs and lettering, Kenilworth Castle, c1570-1

Fig 13: Ragged Staff graffiti from Hampton Court Palace, probable sixteenth century

Fig 14: The Dudley graffiti at the Tower of London, c1553-4

Fig 15: The Smythson Plan, Warwick Castle, c1600

Fig 16: Detail of the probable foundations of Ambrose Dudley’s timber lodgings, The Smythson Plan, c1600

Fig 17: Floor Plan of Kenilworth Castle, showing Leicester’s Building adjoining the medieval chambers, © English Heritage

Fig 18: Surviving exterior of Leicester’s Building

[i] The discussion of historic plasterwork is taken from Dr Gapper’s PhD, found on her website. https://clairegapper.info/ [accessed 18/06/2025]

[ii] Richard Haydocke, A tracte containing the artes of curious paintinge caruing buildinge, (Oxford, 1598), pp68-69

[iii] I’m grateful for Dr Gapper’s analysis of the Warwick fragment. Her PhD can be found online here: C. Gapper, ‘Decorative Plasterwork in City, Court and Country, 1530-1640’, PhD, (Courtauld Institute of Art, 1998), https://clairegapper.info/from-timber-to-plaster.html#_edn77

[iv] The majority are now kept at the V&A, and only a few fragments have come from ceilings.

[v] BL Add. 48976 ff. 5-9

[vi] The Romance of Guy of Warwick, ed. J. Zupitza, Vol.2, (London, 1887), p315, E. Mason, ‘Legend of the Beauchamp Ancestors: The Use of Baronial Propaganda in Medieval England’, Journal of Medieval History, Vol.10, No1, (1984)

[vii] The first mention of Guy of Warwick relics is in Thomas Beauchamp the elder’s will, see W. Dugdale, The Antiquities of Warwickshire illustrated, London, 1656), p317

[viii] Ibid., p323, The Black Book of Warwick, ed. By T. Kemp, (Warwick, 1898), p36

[ix] Manuscripts of the Marquis of Salisbury, Vol.11, p433

[x] A. Stewart, Philip Sidney: A Double Life, (London, 2000), Chapter 2

[xi] Warwickshire Feet of Fines, ed. L. Drucker, Vol.3, (Oxford, 1944), no2683. Summary in M. Hicks, Warwick the Kingmaker, (Oxford, 1998), p225

[xii] TNA SP10/1, fol.10

[xiii] D. Loades, ‘Dudley, John, duke of Northumberland (1504-1553), Oxford DNB, S. Adams, ‘Dudley, Ambrose, earl of Warwick (c1530-1590), Oxford DNB

[xiv] TNA LR2/120, fol.31

[xv] S. Adams, ‘”because I am of that Countrye and Mynde to Plant Myself there”: Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and the West Midlands’, Midland History, Vol.20, No.1, (1995), pp31-32

[xvi] S. Adams, Household Accounts and Disbursement Books of Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester, vol.6(Cambridge, 1995), p425

[xvii] E. Goldbring, ‘The earl of Leicester’s inventory of Kenilworth Castle, c.1578’, English Heritage Historical review, Vol.2, (2007), pp[REF]

[xviii] G. Parry & C. Enis, Shakespeare before Shakespeare: Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, and the Elizabethan State, (Oxford, 2020), Chapter 1

[xix] C. Enis, ‘Edward Arden and the Dudley earls of Warwick and Leicester, c1572-1583’, British Catholic History, Vol.33, No.2, (2016), pp170-210

[xx] WCRO CR1886/C4/18

[xxi] Black Book of Warwick, pp42-43

[xxii] Ibid., pp227-313, summary in Parry & Enis, Shakespeare, Chapter 1

[xxiii] ‘The borough of Warwick: The castle and castle estate in Warwick’, in A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 8, the City of Coventry and Borough of Warwick, ed. W B Stephens (London, 1969), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/warks/vol8/pp452-475 [accessed 1 July 2025]

[xxiv] The Itinerary of John Leland in or about 1535-1545, ed. L.T. Smith, Vol.2, (London, 1908), pp40-1

[xxv] Letters and Papers Henry VIII, Vol.11, pp172-173

[xxvi] Cal S.P. Dom Edward VI, p3

[xxvii] TNA LP2/255, fol.97

[xxviii] The tower was probably named in the wake of John Stow writing how ‘Julius Cæsar, the first conqueror of the Britons, was the original author and founder as well thereof, as also of many other towers, castles, and great buildings within this realm’, see J. Stow, ‘Of Towers and Castels’, in A Survey of London. Reprinted From the Text of 1603, ed. CL Kingsford (Oxford, 1908)

[xxix] R.K. Morris, ‘”I was never more in love with an olde howse nor never newe worke coulde be better bestowed”: The earl of Leicester’s remodelling of Kenilworth Castle for Queen Elizabeth I’, The Antiquaries Journal, Vol.89, (2009), p299

[xxx] Salisbury Manuscripts, p433, WCROCR1886/C4/18, TNA LP2/255, fol.97

[xxxi] See Morris, ‘The earl of Leicester’s remodelling of Kenilworth Castle;, pp241-305

[xxxii] Cited in C. Gapper, ‘Decorative Plasterwork in City, Court and Country, 1530-1640’. PhD, (Courtauld Institute of Art, 1998), https://clairegapper.info/from-timber-to-plaster.html#_edn77

[xxxiii] E. Goldring, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and the world of Elizabethan Art, (London, 2014), pp180-184

[xxxiv] G.M.D Booth & N. Palmer, Warwick Castle Watergate Tower: A Documentary and Pictorial Survey, (1996), pp2-3

[xxxv] M. Binney, ‘Warwick Castle Revisited III’, Country Life, (1982)

[xxxvi] Black Book of Warwick, p95

[xxxvii] The room is described as ‘the new dyninge chamber’ in Fulke Greville’s will, c1630, P. Sands, Transscripts of the papers of Fulke Greville, (Studley, 2016), p63. Fulke Greville’s father was recorded as a guest at the Queen’s visit to Warwick, Ibid., p96

[xxxviii] Ibid.

[xxxix] J.C. Rogers, ‘The Manor and Houses of Gorhambury’, St Albans and Harts Architectural and Archaeological Society, (London, 1936),p47

[xl] I. Dunlop, Palaces and Progresses of Elizabeth I, (London, 1962), pp119-20

[xli] Examples cited from M.H. Cole, The Portable Queen: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Ceremony, (Massachusetts, 1999), pp84-96

[xlii] T. Kemp (ed.), The Black Book of Warwick, (Warwick, 1898), p90