Warwick Castle’s Oubliette: The TRUTH!

2 April 2025

Type ‘Warwick Castle’ into Google, X, Instagram or any other search engine and you’ll discover one story repeated again and again. It has become the emblematic narrative of the castle, its history, and the zeitgeist of its’ owners’ strategic vision.

This is the so-called ‘Oubliette’ which, according to one possible AI-generated X post, describes how:

“The lower dungeon of Warwick Castle features an ancient chamber known as an “Oubliette”, where prisoners were abandoned and left to be forgotten. An oubliette is characterized by its concealed location, accessible solely through a trapdoor or ceiling. These hidden dungeons were prevalent in medieval castles…the term “oubliette” finds its origins in the French word “oublie”, which translates as “forget”.

It is a story now oft repeated in TV documentaries, travel guides, anthologies of medieval history, local Facebook groups, and even by well-known history influencers. The oubliette, in the sideroom of what is now referred to as the Gaol, has become the iconic architectural feature of this incredible building. What few (and there are a notable few) fail to question is what evidence survives not only for the architectural and cultural existence of an oubliette at Warwick, but the narrative history of the oubliette too. Here, I share my thoughts….

Architectural evidence

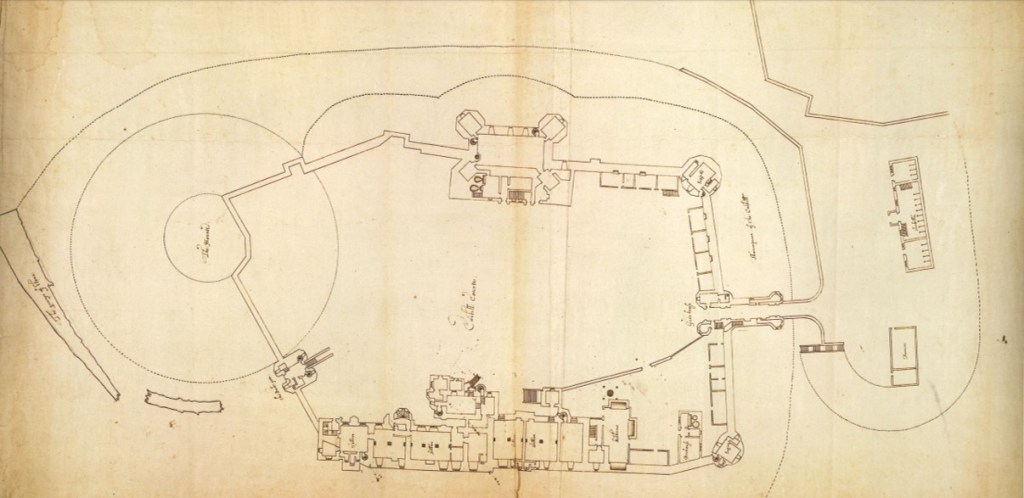

The ‘Gaol’ is found in the basement of Caesar’s Tower, the earliest of the magnificent east range constructed in the late fourteenth century, presumably commissioned by Thomas Beauchamp the elder, earl of Warwick before his death in 1369, and completed under the tenure of his son, Thomas Beauchamp the younger. The tower has eight distinctive levels: three accommodation floors, three battlement levels at the summit, a ground floor storeroom, and the basement. A seventeenth century tradition supposed the original tower was called ‘Poitiers Tower…from prisoners brought hither out of France’; the name Caesar likely a sixteenth century aberration when the Dudley earls of Warwick, who exaggerated the earldom’s ancient origins, reinvented a Roman origin story for the castle and earldom.[i]

The original basement was accessed from a Service Yard, shown in detail on a plan made by Robert Smythson in c1600 which most likely reflected the functional use of the area in the fourteenth century.[ii] An independent kitchen block, with three large roasting fires, a brewhouse, and what appears to be a well-house connected to the main apartments from a single stairwell; a long timber-framed wall conceals the service yard from the outer castle courtyard. Cellars and what must be servant lodgings beneath the main apartments were connected from an independent entrance outside the service yard. The basement was isolated between the brewhouse on the south wall and a timber-framed building, presumably storerooms, to the east.

The straight stairwell leading down to the basement opens out into two levels, an upper level lit from a thin, square window overlooking the river, and a large lower level with a side room. The main room is vaulted, lit from a small shaft in the west wall. A side room on the south wall, the location of the supposed ‘oubliette’, shares the same dimensions and orientation as the garderobes on the upper floors. Inside the ‘oubliette’ void are two further shafts that are located in the exact positions of the two upper floors with garderobes, most likely rendering this void beneath the basement a cesspit.

In the last decade, architectural historians have pondered the original purpose of the basement. Despite the assertions from Warwick Castle guidebooks and various social media posts, a landmark survey undertaken in 2014 by Andrew Parkyn and Tom Mcneill offered the probable intention. The entry to the basement from the Service Yard shows no evidence of a door-check or a drawbar, suggesting there was no attempt to control security or access in or out. This discounts not only the likelihood of its use as a dungeon but also as a cold storeroom. The inclusion of a garderobe also makes the likelihood of a cold store low.

Altogether, the architectural evidence suggests a cold, damp and dark space intended for use by servants for long periods of time, where access in and out was liberally open; Parkyn and Mcneill suggested that it was a place where servants were expected to be working with water for many hours at a time; a diary for producing milk, butter and other sundries the most likely original function of the basement of Caesar’s Tower.[iii]

Documentary evidence

What evidence exists to suggest Caesar’s Tower and its basement may have been a dungeon with an oubliette? Few archival details of Caesar’s Tower survive before the sixteenth century. Scattered medieval references to ‘the gaol of Warwick Castle’ are likely to be misrepresentations by court recordkeepers, who expected gaols to be inside castles like York (Warwick’s common gaol was in the town centre) rather than any definitive evidence of the castle’s regular use to incarcerate prisoners.[iv] Where evidence of castle prisoners exist, they are often high profile noble captives personally held on behalf of the Warwick earls, perhaps deemed unfit for a common gaol; Piers Gaveston in 1312, Henry Beaumont in 1326, or Edward IV in 1469, for example.

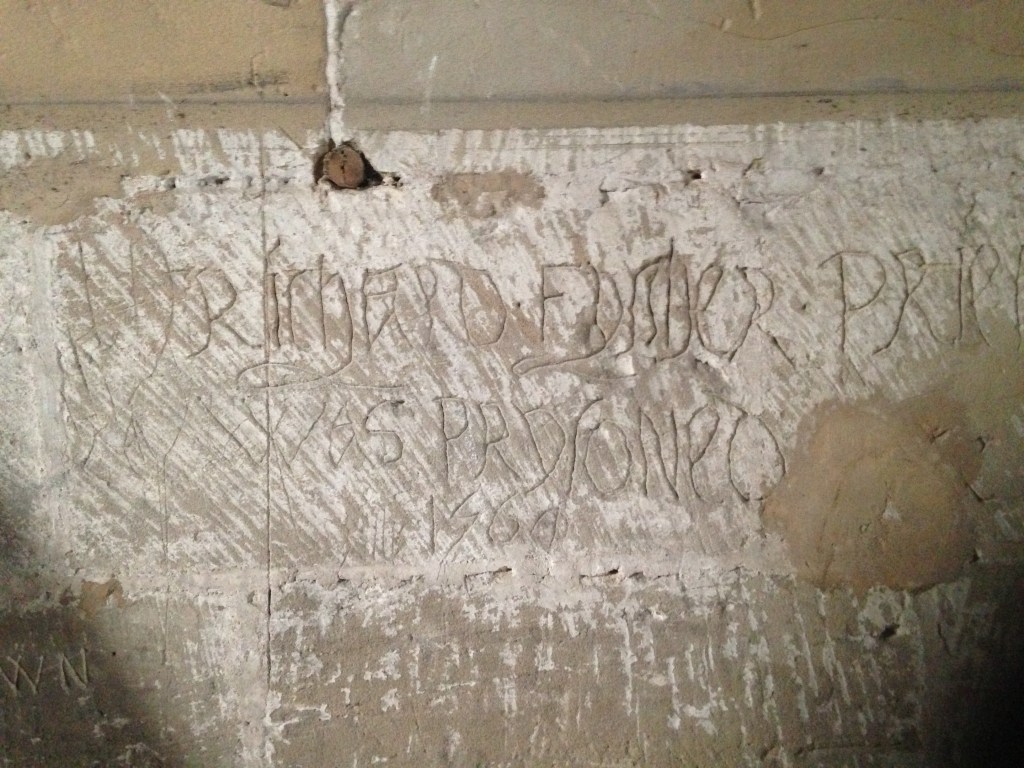

In the late sixteenth century, when the castle was largely unoccupied but for a skeleton staff, Caesar’s Tower does appear to have served as an overflow for the common gaol: ‘an uncouth prison of felonious persons clogged with fetters and bolts of iron’, as one seventeenth century genealogist described.[v] It might be a tad overblown; such exaggeration served the needs of Sir Fulke Greville and his heirs, who claimed stewardship after 1604 on the grounds of saving the castle from collapse. Their major conservation and renovation work between 1605-15 were trumpeted by successive generations. That being said, the second floor of Caesar’s Tower contains a remarkable graffiti mark reading: ‘Richard Fysher priest was prisoned here 1560/4’ which suggests at least some prisoners, perhaps those who required low security, were held in Caesar’s Tower during the sixteenth century.

The first, indeed only, evidence of general imprisonment at Warwick Castle dates from the period of the British civil wars. Between 1642 and 1660, the castle was ruled by a particularly zealous sect of Parliamentary forces in the civil war against militias loyal to Charles I. Spearheaded by Robert lord Brooke, and then by his trusty subordinates John Bridges, Joseph Hawkesworth, and William Purefoy, the garrison was alive with radical Puritanism and Warwick a town under military occupation. Scores of graffiti inside the three main towers date from this period, when prisoners were kept at the castle until at least 1651. While many of these were Royalist soldiers, including the noble figureheads the earls of Lindsay and Holland, others were traders, merchants and travellers who were held captive until a ransom was paid.

In one account, a Thomas Peers of Alveston, a Catholic landowner, was captured on his estates after refusing to provide a Captain Ingram from the Warwick Castle garrison with £100 to save his life. A later account revealed:

“[He was] then hauled by Ingram to Warwick Castle. There he remained some time, during which, to toll him on to a fuller ransom, he had some freedom, as of walking about the castle and town, which nevertheless cost him dear…he was about the end of the last week threatened with the dungeon, and was accordingly cast into it…where in a few days, what with want of sustenance and the noisiness of the stinking vault, he died a true patient of those cruelties.”[vi]

Another account of three Quakers, in the 1650s, were said to be ‘taken to the dungeon in Warwick Castle twenty steps under Ground.’[vii]

These are likely the earliest references to a dungeon in the basement of Caesar’s Tower. The inference being that the ‘stinking vault’ was used as the harshest punishment for those local captives who refused, or were unable, to pay a ransom for their freedom, and particularly for Catholics and other dissidents – the sheer volume of religious graffiti in the basement would seem to support this hypothesis.

It is almost certain that it is this legacy, a chamber used by zealot Puritans to imprison Catholics and dissidents during the British civil wars of the 1640s, that has survived through to the present. But, returning to the original question, what about the oubliette?

The Advent of Mass Tourism

There is a hint in the above documentary evidence of the ‘forgotten’, though it is no more than skin-deep. The evidence demonstrates that if prisoners were given freedom to roam the castle, and even the town, for a fee then presumably the same would be for those who ended up inside the dungeon.

So, one question I’ve been asking recently which it appears no-one seems to ask when coming back to the Oubliette: when was the ‘oubliette’ first mentioned?

‘Oubliette’ was a term associated with medieval imprisonment, and indeed it was a term often applied to punishment of prisoners, particularly those condemned by the Catholic Church in France. But the punishment of being ‘forgotten’ did not necessarily imply a physical, solitary confinement in a tower. The French tradition for gaols to be underground, often in large pits beneath towers and castles, may have been muddled with the idea of ‘oubliette’ in later interpretations and misreadings by nineteenth and early twentieth century historians.[viii]

So, to come back to the Warwick Castle oubliette. An interesting source for the castle’s oubliette history are guidebooks; as a major attraction, the castle’s ‘dungeons’ have often been used to drive tourism. When did the oubliette first get mentioned? The earliest known guidebook, written in 1815, described:

“a dungeon, deep, damp, and dark; exhibiting a horrible specimen of a place of subterraneous imprisonment. One small loop hole admits its only light; insufficient by tracing the large letters and figures, still visible by the help of a candle on the wall. One of the more legible of these inscriptions records the confinement of a Royalist soldier…”[ix]

No oubliette. That trend continued through the nineteenth century, during which time the dungeon earned the anachronistic name of ‘Piers Gaveston’s dungeon’ and into the twentieth century[x], as guidebooks described:

“the lower stage of Caesar’s Tower, which is now closed to the public, and from this, sixteen more [stairs] conduct to the floor of the dungeon, which is four or five feet below the general court. On the walls near the window and door are rudely scratched letters, drawings of bows, crucifixes etc. now nearly obliterated by damp…”[xi]

The focus on graffiti, and damp, continued through the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s; in fact, one has to open a newly published guidebook from 1973, with the imposing Caesar’s Tower on its front cover, to find the very first reference to Warwick’s oubliette:

“The Dungeon is entered from the castle’s inner courtyard by a flight of 27 narrow steps. One small loophole gives both ventilation and light…the dungeon has an unusual feature in its oubliette, a dungeon within a dungeon, where the unhappy prisoner had just sufficient room to lie in complete darkness.”[xii]

Why 1973? Warwick Castle’s fortunes took a turn after 1968, when the day-to-day business of the building was handed from the earl of Warwick, a former Hollywood actor who had grown weary of British life, to his son ‘Brookie’, or lord Brooke, who planned to revolutionise the castle’s operations to match the enormous success of the stately home business of the 1960s, led by the enigmatic lords Montagu, Bath, and Bedford. For this, he assembled a new team to manage the castle’s public displays – displays which had been largely unchanged since the nineteenth century. First, there was a new curator Paul Barker (image below), a fifty-year-old eccentric former soldier from the Warwickshire Yeomanry, who abandoned his Hull accent for the prose and appearance of a Victorian butler.

The other key figure was Gordon Cook, a former Grenada television producer who had been the figurehead of major changes in the way stately homes welcomed visitors, namely through the lens of entertainment. After five years as general manager of Beaulieu, he took on the role of general manager at the castle in 1968.

Cook transformed the castle into an attraction. He opened a new ticket office, public toilets and a café in the Conservatory, gift shops in the chapel vestry, and worked closely with Barker to shift the castle’s interpretation from stately home and art collection to a place of knights, battles, and torture. There were fighting knight shows, a new ‘Ghost Tower’, ‘attack and defence’ talks, and the Sealed Knot society annually performed re-created sieges. As the 1973 guidebook went on:

“In the vaulted fourteenth century chambers immediately above the Dungeon there is a grisly display of torture instruments. A number of the exhibits are from the famous Nuremburg Castle collection and there is also a selection of pictures and engravings illustrating the use of these barbarous instruments.”

The guidebook failed to mention many of the ‘medieval torture instruments’ had in fact been purchased from sex shops in Amsterdam the previous year!

The reopening of the Dungeon to the public, and the sudden ‘discovery’ of a medieval oubliette belong to this same drive to reinvent the castle’s public image as a place of medieval barbarism. It was enormously successful, of course, with visitor numbers rising from around 250,000 in 1966 to 400,000 in 1973, and reported hour-long queues to get inside the Dungeon to see the oubliette.

This commercial genius, this reinvention of myths as fact, it seems, continues to have enormous influence: today, the Castle Dungeon experience (located in the seventeenth century Brewhouse) leans heavily into the gruesome, the macabre, and the melodramatic, while the basement of Caesar’s Tower, used briefly for Catholic prisoners in the 1640s, shall now forever be associated with torture, punishment, and the invention of an ‘oubliette.’

I suppose it’s a bit more exciting than a medieval dairy!

[i] The Genealogie, Life, and Death of the Rt Hon Robert Lord Brooke Baron of Beauchamps Court in the Countie of Warwicke, (London, 1643), Naming towers after Caesar is described by the sixteenth century writer John Stow, who wrote ‘Julius Cæsar, the first conqueror of the Britons, was the original author and founder as well thereof, as also of many other towers, castles, and great buildings within this realm’, see J. Stow, ‘Of Towers and Castels’, in A Survey of London. Reprinted From the Text of 1603, ed. CL Kingsford (Oxford, 1908)

[ii] RIBA, RIBA29130

[iii] A. Parkyn and T. Mcneill, ‘Regional Power and the Profits of War: the East Range of Warwick Castle’, Archaeological Journal, Vol.169, No.1, pp480-518

[iv] For example, CPR 1364-67, 20 January 1367 ‘Pardon to Adam Fisher of Assho for the death of Richard Taillour, as the king learned from Thomas Ingelby, justice to deliver the gaol of Warwick Castle, that he killed him in self-defence.’

[v] The Genealogie, Life, and Death of the Rt Hon Robert Lord Brooke Baron of Beauchamps Court in the Countie of Warwicke, (London, 1643)

[vi] TNA E247/26

[vii] Cited in P. Tennant, Edgehill and Beyond: The People’s War in the South Midlands 1642-1645, (Banbury, 1992), p226

[viii] See R. Telliez, ‘Jails, pits, dungeons…’, in J. Claustre, I. Heullant-Donat, and E. Lusset (eds), Lockdowns Vol.1: The cloister and the prisoner, 6th – 18th century, (Paris, 2021), pp169-182

[ix] An Historical and Descriptive Guide of the Town and Castle of Warwick, ed. H. Cooke, (Warwick, 1815)

[x] F. Warwick, Warwick Castle and its Earls, Vol.1, (London, 1903), p85

[xi] Warwick Castle and Town together with Guy’s Cliffe, (Leamington Spa, 1930)

[xii] Warwick Castle Guidebook, (Norwich, 1972)

Leave a comment